In 1923, when the Secrets of Nature series was in its second season, British Instructional Films released a film with the intriguing title of Strange Friendships. Behind this film is a fascinating story about animal intimacy and gender in interwar Britain. I briefly wrote about this in an article that I published last year, but I thought it would be nice to elaborate a little bit here.

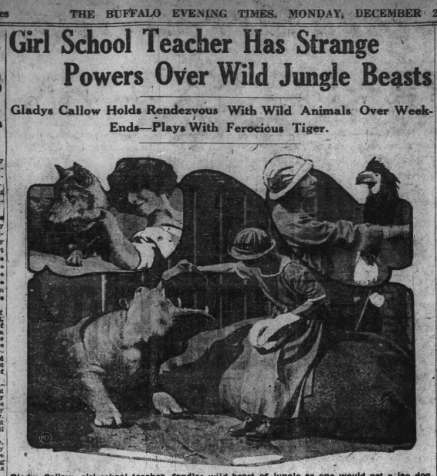

At the heart of the story is a woman with a name worthy of Hollywood stardom: Gladys Callow. Her claim to fame was an uncanny ability to get up close to numerous zoo animals at the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) public gardens in Regent’s Park. There, she often had her picture taken alongside her animal “friends”, with the images finding their way into the press on several occasions. Newspapers in the 1920s were beginning to fill their pages with more and more photographs, vying for the attention for a growing reading public, and pictures of animals were an easy way to appeal to these new readers – many of them women.

“How is it done?”, Callow remarked in a rare interview. “I cannot tell you. Ever since I was a child I have loved animals. I do not fear them and they do not seem to fear me. I always make a habit of talking to them, avoiding jerky movements and treating them as one would treat a domestic pet.” (Weekly Dispatch, 28 October 1923).

Gladys Maud Callow was born on 1 July 1894, in the London borough of Paddington (now part of Westminster). Her father, James William, was a watch and clock repairer who worked on his own account. This was very much a family business – when Gladys’s father passed away in 1920, his widow Florence Ada became not only head of the household: she also continued the work of her late husband, listing her occupation in the 1921 census as ‘Practical watchmaker’s and jeweller’s business’. Glady’s younger brother Douglas James, appears in the same census as an apprentice to the family business, while the middle child, Dorothy, was working as a book-keeper for another company.

In 1921 Gladys, then twenty-six years old, was still living with her mother and siblings at the family home on Shirland Avenue, just to the north of Paddington station. On Charles Booth’s colour-coded maps of London, produced in 1889, this area is coloured with a mixture of light and dark reds: this was a middling neighbourhood, with a mixture of middle-class and working-class families. By that time Callow was an elementary school teacher at Stonebridge School in Harlesden, about three and a half miles north-west from her home. Thanks to an article published in the Kensington Post, we know that Callow was still teaching there in March 1928.

As is often the case with women whose contributions have been overlooked, piecing together details about Callow’s life is not always straightforward. Most of what we know about Callow comes from newspapers and magazines that described her unusual ability to get up close to dangerous animals held in the enclosures at London Zoo. These often referred to her as an “animal charmer” (Weekly Dispatch, 28 October 1923) possessing “extraordinary powers” (Kensington Post, 15 March 1928), and stories about her were printed as far away as Canada and the United States.

Two things are noteworthy about this. The first is that pictures of Callow were often published or displayed in public by J. E. Saunders, a well-known zoo photographer who was behind all of the pictures of Callow that I know of. In the 1920s he toured different parts of the country showing lantern slides of his photographs, and also published several essays in The Photographic Journal, which was published by the Royal Photographic Society. The second is that the way these images were presented to readers was left largely to the discretion of journalists and editors, who in most cases looked for the most attention-grabbing framing they could find.

Both of these things contributed to the highly gendered way in which people viewed Callow’s relationship to the animals she was pictured with. Saunders, for instance, confessed that he had a “somewhat cynical attitude to women”, and attributed Callow’s “unusual talent” and “uncanny knowledge” to the fact that “many of the animals in the

Zoo were accustomed to female domination”. In other words, Callow’s sense of comfort had little to do with her own abilities, and everything to do with her gender. Newspapers picked up on this suggestion too, describing the animals as “henpecked”. This characterisation of Callow’s unusual skill is redolent of beliefs about the connection between women and the natural world which stretched back a long way: the belief, in short, that they were ‘closer’ to nature.

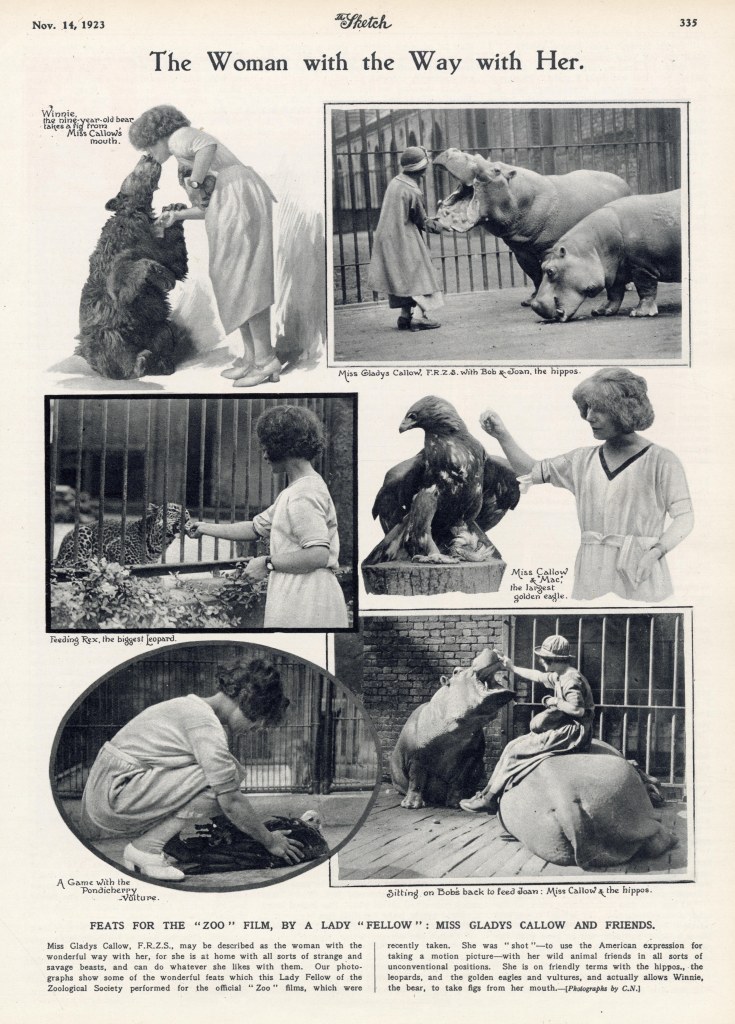

A montage of six photographs of Callow, published in The Sketch in 1923, noted that the film Strange Friendships was in production. Although a master copy of the film is held by the BFI, I have not been able to obtain permission to view it so far. However, these images give us a sense of the sort of thing the canister might contain. Callow is pictured pictured with a bear, two hippopotamuses, a leopard, a golden eagle, and a vulture. In one of these images, in the top left, she was captured ‘kiss feeding’ an American black bear. Named Winnipeg and hailing from Ontario, the bear is better known for inspiring A. A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh (1926). Callow is dressed fashionably although somewhat simply, usually wearing a white dress which makes her stand out from the animals she poses with, and often sporting an assortment of different hats. Her position in these images is a striking symbol of the clashing of settings that Zoos exemplified in this period – animals, brought from distant locations often subjected to colonialism, brought to the imperial metropolis under the guise of science to be exhibited to urban audiences.

Interestingly, Callow was keen to emphasise that her proximity to the zoo animals was no mere frivolous pastime. In fact, her ability to get up close to some of the world’s most dangerous animals could often prove useful to the zoo authorities. For instance, speaking at Stonebridge School’s evening institute in 1928, she cast herself in the role of nurse, telling of one case where she had been able to pacify a young lion who the keepers had been too scared to approach, identifying and curing a toothache that was bothering it. On a separate occasion she claimed to have treated a “septic tooth” on a hippo (Weekly Dispatch, 28 October 1923). This nursing role is evident in many other images of Callow, where she is often cradling, feeding, or stroking the animals in question.

That she wished to be viewed as more than a mere zoo visitor, moreover, is evident by the way that she was often described as a “Lady Fellow” of the Zoological Society of London. While fellowship of the society was really little more than a paid membership, to readers it might have suggested a closer relation to the institution. To date, I have not found much evidence to tell us what the zoo authorities thought of Callow. That she was friendly with the zoo keepers, who permitted her to enter the enclosures with such frequency, is clear, and on one occasion she offered a public demonstration of her talents, presumably with the consent of the ZSL. At the very least, it seems likely that they viewed the publicity that she brought to the zoo as a net positive. Callow didn’t only have her picture taken in London, moreover – several of Saunders’s pictures also captured her alongside animals at Clifton Zoo in Bristol.

In her 1928 talk at Stonebridge School, Callow also said that she had “recently” saved a cameraman’s equipment from trampling by giraffes. This is significant because it suggests that Callow was present for filming at the London Zoo beyond her involvement in the 1923 film for Secrets of Nature – allowing us speculate that her presence was helpful in shooting further animal sequences for the series.

In fact, it seems that Callow may have initially discovered her talents precisely in order to facilitate the taking of images. In an article in The Photographic Journal, Saunders explained that the animals were often “too friendly to allow themselves to be photographed as he would like to photograph them, and so he had to get Miss Callow to manage them if they were to be photographed at all by him” (The Photographic Journal, February 1926). For Saunders, the “friendships” that he and Callow established with the zoo animals were fundamental to the kinds of pictures that they took together, allowing them to produce “portraits instead of mere snapshots” (Illustrated Leicester Chronicle, 6 March 1937).

Callow, however, was not only a model. In an article for Kodak Magazine in 1926, she wrote about her own experience of taking pictures at the zoo using a Graflex camera: clearly the manufacturers believed that her endorsement would help stimulate sales. In her article, Callow describes herself entering the cages of a Bateleur eagle, a Pondicherry eagle, a hornbill and a lion, always referring to the animals by name and emphasising her long association with them (“The lion cub was easy – she knows me well”.)

In 1939, Gladys Callow was still living on Shirland Avenue with her mother. Her sister Dorothy, who married Sidney A. Coates in 1922, had moved with her husband to Harrow. Her brother, too, relocated to Harrow too with his wife Lily, and now worked as a ‘General Hand Labourer’. This left Gladys alone to look after their mother, who died in 1949. I have been unable to find much about Callow’s life thereafter, other than that she passed away in Brighton in 1977, having lived there since at least the early 1960s.

There are many things that I would like to know about Callow’s life that are not registered in the archives. Did her new neighbours in Brighton know about her brief fame as an animal whisperer? Did she continue to visit zoos later in life, making friends with the animals? Did she have any animals of her own? Did she ever have a partner or a lover? These questions about a fascinating and forgotten historical figure will have to remain unanswered. Instead, we are left with a series of images that are as playful as they are enigmatic, offering a glimpse into the popular culture of animals in 1920s Britain.